Introduction to ScoreDraft

The source-code of ScoreDraft is hosted on GitHub, where you can always find the latest changes that I have made.

PyPi packages for Windows x64 & Linux x64 are available for download by

pip install scoredraft

This document will introduce the uses of each basic elements of ScoreDraft.

HelloWorld Example (using TrackBuffer)

Let’s start from a minimal example to explain the basic usage and design ideas of ScoreDraft.

import ScoreDraft

from ScoreDraft.Notes import *

seq=[do(),do(),so(),so(),la(),la(),so(5,96)]

buf=ScoreDraft.TrackBuffer()

ScoreDraft.KarplusStrongInstrument().play(buf, seq)

ScoreDraft.WriteTrackBufferToWav(buf,'twinkle.wav')

Play Calls

ScoreDraft.KarplusStrongInstrument().play(buf, seq)

As the most important interface design of ScoreDraft, “Play Calls” is a class of commands of the form:

instrument.play(buf,seq)

which simply means, play sequence seq with the instrument and write the resulted waveform to “buf”.

Similarly, you can also use a percussion group to play or use a “singer” to sing. We will use the term Play Call to refer to any command of these sorts.

We will sometimes pass in tempo and reference frequency parameters into a Play Call. There are built-in default values for these parameters so they are not compulsory.

Imports

import ScoreDraft

from ScoreDraft.Notes import *

The first thing to do is to import “ScoreDraft” package, which provides the core Python interfaces of ScoreDraft.

Most application code will also import the note definitions from the “ScoreDraft.Notes” module. In fact, the core interface of ScoreDraft does not include any specific definition of musical notes. It simply accepts a physical frequency f_ref in Hz as a reference frequency for each Play Call, and a relative frequency f_rel[i], which is just a multiplier, for each note. The physical frequency of each f_note[i] can be then calculated by:

f_note[i] = f_ref *f_rel[i].

In the note definition module ScoreDraft.Notes, a bunch of note functions do(), re(), mi(), fa() are defined to convert musical language to physical numbers. These functions are really simple in nature, thus allowing user to easily modify or extend for special purposes, such as when an alternative tuning (other than 12-equal-temperament) is desirable.

Score Representation

seq=[do(),do(),so(),so(),la(),la(),so(5,96)]

The score itself is represented as a set of Python lists, called sequences. How theses sequences are formed will be explained in the succeeding sections.

The elements of the sequences are processed consecutively, but generated sound can overlap with each other by containing backspace operations in the sequences.

Because the sequences are just Python lists in nature, the full function set of Python can be utilized to automate the score authoring work. Explaining those tricks may require a separate document.

TrackBuffer

buf=ScoreDraft.TrackBuffer()

ScoreDraft uses track-buffers to store wave-forms. A track-buffer can be used as either an intermediate storage for synthesis result or the final buffer for the mix-down result of several intermediate buffers.

The package ScoreDraft provides a class TrackBuffer, which is a direct encapsulation of the C++ interface. Comparing to the class Document (to be introduced later), class TrackBuffer is a low-level interface.

HelloWorld Example (using Document)

import ScoreDraft

from ScoreDraft.Notes import *

doc=ScoreDraft.Document()

seq=[do(),do(),so(),so(),la(),la(),so(5,96)]

doc.playNoteSeq(seq, ScoreDraft.KarplusStrongInstrument())

doc.mixDown('twinkle.wav')

Most musical pieces need multiple track-buffers. The class ScoreDraft.Document is provided as an unified track-buffer manager, and it is more recommended than using ScoreDraft.TrackBuffer directly.

As shown in the above example, using class Document is accompanied by some changes in the writing style of the Play Calls. When issuing a Play Call through the class Document, the target track-buffer is always implicated, so a parameter is not necessary anymore. At the same time, the instrument used for playing becomes a parameter. The format now looks like doc.play(seq,instrument) instead of instrument.play(buf,seq).

There are a few benefits. First, it simplifies the creation of track-buffers, the document object can do that for you implicitly during Play Calls. Second, it largely simplifies the mixdown call. You don’t need to enumerate all the track-buffer to be mixed when they are managed insides the document object. Third, visualization component can exploit polymorphism by replacing the Document class with an extended version. For example, the Meteor visualizer can be enabled with minimal effort by replacing ScoreDraft.Document with ScoreDraft.MeteorDocument.

The class Document also manages tempo and reference frequency parameters internally, so we don’t pass them through the Play Calls anymore in this case.

Initialization of Intruments/Percussions/Singers

User can always run the PrintCatalog.py to get a list of all available instrument/percussion/singer initializers.

# PrintCatalog.py

import ScoreDraft

ScoreDraft.PrintCatalog()

The output will look like:

{

"Engines": [

"KarplusStrongInstrument - Instrument",

"InstrumentSampler_Single - Instrument",

"InstrumentSampler_Multi - Instrument",

"PercussionSampler - Percussion",

"SF2Instrument - Instrument",

"UtauDraft - Singing"

],

"Instruments": [

"Ah - InstrumentSampler_Single",

"Cello - InstrumentSampler_Single",

"CleanGuitar - InstrumentSampler_Single",

"Lah - InstrumentSampler_Single",

"String - InstrumentSampler_Single",

"Violin - InstrumentSampler_Single",

"Arachno - SF2Instrument",

"SynthFontViena - SF2Instrument"

],

"Percussions": [

"BassDrum - PercussionSampler",

"ClosedHitHat - PercussionSampler",

"Snare - PercussionSampler",

],

"Singers": [

"Ayaka_UTAU - UtauDraft",

"GePing_UTAU - UtauDraft",

"jklex_UTAU - UtauDraft",

"uta_UTAU - UtauDraft",

]

}

The first list Engines gives a list of names of available engines and the type of engine (is it an instrument or percussion or singing engine?).

The 3 succeeding lists gives names of ready-to-use instrument/percussion/singer initializers and the engines they are based on. ScoreDraft creates these initializers automatically at starting time by searching some specific directories for samples/banks based on the starting place of the Python script.

The definitions of the initializers are dynamic code blocks, you cannot find them in the source-code. However, using them is simple. For example you can initialize a Cello instrument by:

Cello1 = ScoreDraft.Cello()

Instrument Sampler

The instrument sampler engine uses one or multiple wav files as the input to create an instrument. The .wav files must have one or two channels in 16bit PCM format. The algorithm of the instrument sampler is by simply stretching the sample audio and adding a envelope. So be sure that the samples have sufficient lengths.

Single-sampling

You can use the class ScoreDraft.InstrumentSampler_Single to create an instrument directly. At creation time, you need to provide a path to the wav file. The path can be either absolute path or relative to the starting folder.

flute = ScoreDraft.InstrumentSampler_Single('c:/samples/flute.wav')

You can also put the wav files into the InstrumentSamples directory under the starting directory so that ScoreDraft can create an initializer for you automatically. The file name without extension will appear as the initializer name in the PrintCatalog lists.

Multi-sampling

You can use the class ScoreDraft.InstrumentSampler_Multi to create an instrument directly. At creation time, you need to provide a path to a folder containing all the wav files of an instrument. The audio samples should span a range of different pitches. The sampler will generate notes by intepolating between the samplers according to the target pitch.

guitar = ScoreDraft.InstrumentSampler_Multi('c:/samples/guitar')

You can also create a subdirectory under the InstrumentSamples directory and put in all the wav files for the instrument. Then ScoreDraft will automatically create an initializer for you using the subdirectory name as the initializer name, which will appear in the PrintCatalog lists.

SoundFont2 Instruments

ScoreDraft contains a SoundFont2 engine. You can use the class ScoreDraft.SF2Instrument to load a SoundFont. Just provide the path to the .sf2 file and the index of the preset you want to use:

piano = ScoreDraft.SF2Instrument('florestan-subset.sf2', 0)

The function ScoreDraft.ListPresetsSF2() can be used to obtain a list of all available presets in a .sf2 file:

ScoreDraft.ListPresetsSF2('florestan-subset.sf2')

You can also put the .sf2 file into the SF2 directory under the starting directory so that ScoreDraft will create an initializer for you automatically. The file name without extension will appear as the initializer name in the PrintCatalog lists. Because we need to know which preset to use, a preset_index parameter is still needed when calling the initializer.

SoundFont2 support is based on a porting of TinySoundFont Here I acknowledge Bernhard Schelling for the work!

Percussion Sampler

The percussion sampler engine uses one wav file as the input to create a percussion. The .wav files must have one or two channels in 16bit PCM format. The algorithm of the percussion sampler is by simply adding a envelope. So be sure that the samples have sufficient lengths.

You can use the class ScoreDraft.PercussionSampler to create a percussion directly. At creation time, you need to provide a path to the wav file.

drum = ScoreDraft.PercussionSampler('./Drum.wav')

You can also put the wav files into the PercussionSamples directory under the starting directory so that ScoreDraft can create an initializer for you automatically. The file name without extension will appear as the initializer name in the PrintCatalog lists.

UtauDraft Engine

The UtauDraft engine uses a UTAU voicebank to create a singer.

You can use the class ScoreDraft.UtauDraft directly. At creation time, you need to provide a path to the UTAU voicebank, and optionally a bool value indicating whether to use CUDA acceleration or not. The default is use CUDA acceleration when available. Pass in a False to disable it without attempting.

cz = ScoreDraft.UtauDraft('d:/CZloid', False)

You can also put the voicebank folder into the UTAUVoice directory under the starting directory so that ScoreDraft can create an initializer for you automatically. The subdirectory name + “_UTAU” will apprear as the initializer name in the PrintCatalog lists. (The “_UTAU” posfix exists for some historical reason). If the original sub-folder name is unsuitable to be used as an Python variable name, then you should rename it to prevent a Python error.

The UtauDraft Enigine tries to be compatible with all kinds of UTAU voice-banks, including 単独音,連続音, VCV, CVVC as much as possible. oto.ini and .frq files will be used to understand the audio samples. prefix.map will also be used when one is present.

When using UtauDraft Engine, for 単独音, you can use the names defined in oto.ini as lyrics, just like in UTAU.

For other types of voicebanks, in order to tackle transitions correctly as well as simplifying the lyric input, user should choose one of the lyric-converters to use. Currently there are:

- ScoreDraft.CVVCChineseConverter: for CVVChinese

- ScoreDraft.XiaYYConverter: for XiaYuYao style Chinese

- ScoreDraft.JPVCVConverter: for Japanese 連続音

- ScoreDraft.TsuroVCVConverter: for Tsuro style Chinese VCV

- ScoreDraft.TTEnglishConverter: for Delta style (Teto) English CVVC

- ScoreDraft.VCCVEnglishConverter: for CZ style VCCV English

For setting lyric converter just call singer.setLyricConverter(converter), for example:

import ScoreDraft

Teto = ScoreDraft.TetoEng_UTAU()

Teto.setLyricConverter(ScoreDraft.TTEnglishConverter)

For CZ style VCCV, you need one more call: singer.setCZMode() to let the engine use a special mapping method.

The converter functions are defined in the following form, write your own if the above converters does not meet you requirements:

def LyricConverterFunc(LyricForEachSyllable):

...

return [(lyric1ForSyllable1, weight11, isVowel11, lyric2ForSyllable1, weight21, isVowel21... ),(lyric1ForSyllable2, weight12, isVowel12, lyric2ForSyllable2, weight22, isVowel22...), ...]

The argument ‘LyricForEachSyllable’ has the form [lyric1, lyric2, …], where each lyric is a string, which is the input lyric of a syllable.

The converter function should convert 1 input lyric into 1 or more lyrics to split the duration of the original syllable. A weight value should be provided to indicate the ratio or duration of the converted note. A bool value “isVowel” need to be provided to indicate whether it contains the vowel part of the syllable.

Instrument Play

The kind of sequence used for instrument play is called note sequence. Note sequences are Python lists consisting of tuples in (rel_freq, duration) form, where “rel_freq” is a float and “duration” an integer.

For example:

seq=[(1.0, 48), (1.25, 48), (1.5,48)]

With an existing document object “doc”, you can “play” the sequence using some instrument like following:

doc.playNoteSeq(seq, ScoreDraft.Piano())

The float “rel_freq” is a relative frequency relative to the reference frequency stored in the document object, which can be set with doc.setReferenceFreqeuncy(), and defaulted to 261.626(in Hz).

The duration of a note is “1 beat” when the integer value “duration” equals 48. The document objects manages a tempo value in beats/minute, which can be set using doc.setTempo(), and defaulted to 80. It is also allowed to feed doc.setTempo() with a series of control points, which builds a Dynamic Tempo Mapping, which is to be discussed later.

When ScoreDraft.Notes is imported, we can write the note sequences in a more musically intuitive way:

seq=[do(5,48), mi(5,48), so(5,48)]

The note functions have intuitive names (do(),re(),mi(),fa(),so(),la(),ti()), and they take in 2 integer parameters, octave and duration. The return values are tuples. While the duration parameter is directly passed to the duration component of the returned tuple, the rel_freq component of the tuple is decided by the octave value plus the note function itself. The default octave is 5, which means the center octave. For example, the returned rel_freq of “do(5,48)” will be “1.0”, and rel_freq of “do(4,48)” will be “0.5”.

When rel_freq < 0.0, ScoreDraft will treat the note as some special marker, depending on whether duration>0 or duration<0. When duration>0, it means a rest. When duration<0, it means a backspace. ScoreDraft.Notes provides 2 functions BL(duration) and BK(duration) to formalize these uses. Backspaces are very useful, because when cursor moves backwards, the next notes will be possible to overlap with the previous notes, making representation of chords possible. For example, a major triad can be written like:

seq=[do(5,48), BK(48), mi(5,48), BK(48), so(5,48)]

Percussion Play

For percussion play, first you should consider what percussions to choose to build a percussion group. For example, I choose BassDrum and Snare:

BassDrum=ScoreDraft.BassDrum()

Snare=ScoreDraft.Snare()

perc_list= [BassDrum, Snare]

The kind of sequence used for percussion play is called beat sequence. Beat sequences are consisted of tuples in (percussion_index, duration) form. Both “percussion_index” and “duration” are integers, where “percussion_index” refers to the index in the “perc_list” defined above, and “duration” is the same as instrument play.

Often, we want to define some utility functions to make the writing of beat sequences more intuitive:

def dong(duration=48):

return (0,duration)

def ca(duration=48):

return (1,duration)

Now you can use the above 2 functions to build a beat sequence like:

seq = [dong(), ca(24), dong(24), dong(), ca(), dong(), ca(24), dong(24), dong(), ca()]

With an existing document object “doc”, you can “play” the sequence using “perc_list” like:

doc.playBeatSeq(seq, perc_list)

Singing

ScoreDraft provides a singing interface similar to instrument and percussion play. The kind of sequence used for singing is called singing sequence. A singing sequence is a little more complicated than a note sequence. For example:

seq = [ ("mA", mi(5,24), "mA", re(5,24), mi(5,48)), BL(24)]

seq +=[ ("du",mi(5,24),"ju", so(5,24), "rIm", la(5,24), "Em", mi(5,12),re(5,12), "b3", re(5,72)), BL(24)]

Each singing segment contains one or more lyric as a string, each followed by one or more tuples to define the pitch corresponding to the leading lyric. In the simplest case, one of the tuples can be the same form as an instrument note: (freq_rel, duration). The tuple can also contain multiple freq_rel/duration pairs to define multiple control-points, like (freq_rel1, duration1, freq_rel2, duration2, …). In that case, pitches will be linearly interpolated between control points, and the last control point defines a period of flat pitch. Pitches are not interpolated between tuples. Using ScoreDraft.Notes definitions, you can define a piece-wise pitch curve by concatenating multiple instrument notes, like do(5,24)+so(5,24)+do(5,0), which defines a pitch curve of 3 control points and a total duration of 48.

All lyrics and notes in the same singing segment are intended to be sung continuously. However, when there are rests/backspaces, the singing-segment will be broken into multiple segments to sing. The singing command looks like following, with an existing “doc” and some singer:

# Teto = ScoreDraft.TetoEng_UTAU()

# Teto.setLyricConverter(ScoreDraft.TTEnglishConverter)

doc.sing(seq, Teto)

The piece-wise formed pitch curve can be used to simulate rapping. There is an utility CRap() defined in ScoreDraftRapChinese.py to help to generate the tones of Mandarin Chinese (the 4 tones). An example using CRap():

seq= [ CRap("chu", 2, 36)+CRap("he", 2, 60)+CRap("ri", 4, 48)+CRap("dang", 1, 48)+CRap("wu", 3, 48), BL(24)]

Dynamic Tempo Mapping

Dynamic tempo mapping is used to accurately define the timeline position and tempo of the generated sound.

It works by replacing the tempo term of a Play Call with a Python list of the following form:

tempo_map=[(beat_position_1, dest_position_1), (beat_position_2, dest_position_2), ...]

beat_position_i is a integer that represent a position in the input sequence. It has the same unit as the duration term, where 1 beat is represented by 48.

dest_position_i is a floating point that represent a absolute position on the destination timeline, in the unit of milliseconds.

When there is beat_position_1=0, the starting point of the generated waveform will be aligned with dest_position_1.

When there is not beat_position_1=0, the starting point of the generated waveform is decided by the current cursor position of the destination track buffer.

For beat_position_i, it is suggested to calculate it by calling ScoreDraft.TellDuration(seq), which measures the length of the sequence seq.

For dest_position_i, we often need to measure the target material (audio/video) that we are aligning to, manually.

For example:

seq=[do(),do(),so(),so(),la(),la(),so(5,96)]

buf = ScoreDraft.TrackBuffer()

piano = ScoreDraft.Piano()

tempo_map = [ (0, 1000.0), (ScoreDraft.TellDuration(seq), 5000.0) ]

piano.play(buf, seq, tempo_map)

The about code will generate the sound accurately aligned to the 1s ~ 5s.

Playback & Visualization

ScoreDraft now contains 2 players/visualizers.

PCMPlayer

ScoreDraft.PCMPlayer can be used to play a previously generate TrackBuffer object buf, with or without a display window.

For windowless use:

player = ScoreDraft.PCMPlayer()

player.play_track(buf)

Here play_track() is an asynchronized call, which means that it will return immediately to execute the succeeding Python code after the playback is started. You can continue to submit more track-buffers to be played-back. The track-buffers will be queued and played-back consecutively.

For visualzied use:

player = ScoreDraft.PCMPlayer(ui = True)

player.play_track(buf)

player.main_loop()

main_loop() has to be called in order to make the UI interactive. However, that will make it a synchronized call. If an asynchronized behavior is required, you should instead use ScoreDraft.AsyncUIPCMPlayer:

player = ScoreDraft.AsyncUIPCMPlayer()

player.play_track(buf)

Or more simply:

ScoreDraft.PlayTrackBuffer(buf)

PCMPlayer supports 2 visualization modes:

- Press ‘W’ to show waveform

- Press ‘S’ to show spectrum

Meteor

Meteor can be used to visualize all kinds of sequences while playing-back the mixed track. The easiest way to use Meteor is to use ScoreDraft.MeteorDocument instead of ScoreDraft.Document.The definition of ScoreDraft.MeteorDocument contains all interface as the one defined in ScoreDraft.Document, plus an extra method MeteorDocument.meteor(chn=-1). If you are using ScoreDraft.Document in your old project, you just need to use Meteor.Document to replace it, and call doc.meteor() at the end of the code, the visualizer will thus be activated. Unlike PlayTrackBuffer(), doc.meteor() is a synchronized call. The execution will be blocked until the end of play-back.

MusicXML & LilyPond Support

ScoreDraft supports MusicXML & LilyPond through class MusicXMLDocument. It can be created from a MusicXML file:

doc = ScoreDraft.from_music_xml('xyz.xml')

or from a LilyPond file:

doc = ScoreDraft.from_lilypond('xyz.ly')

To play the notes into the track-buffers, use the playXML() method:

instruments = [ScoreDraft.Piano()]

doc.playXML(instruments)

Each instrument is aligned to a track (staff). If there are fewer instruments than tracks, the last instrument will be used multiple times.

A MusicXMLDocument can be used just like other documents, Meteor is supported by default.

YAML Based Input

We can see that the LilyPond syntax is more compact and easier to write comparing to writing the sequences directly into Python. However, parsing LilyPond is non-trivial. The previous method uses python_ly to first convert ly to MusicXML then reads from the MusicXML format. That process doesn’t always work well. Moreover, there are cases where information useful to the synthesizer engine cannot be included into LilyPond and MusicXML, so we still need extra configurations in our Python code.

Obviously, a trade-off can be made between human-readability and machine-readability. The solution is to use YAML for the outline structure, and LilyPond syntax for notes only, so that we are able to include everything we need for the synthesizer into a single YAML file.

# exmaple 1

score:

tempo: 150

staffs:

-

relative: c''

instrument: Arachno(40)

content: |

r4 g c d

e2 e2

r4 e dis e

d2 c2

r4 c d e

f2 a2

r4 a g f

e2. r4

-

relative: c

instrument: Arachno(0)

content: |

\clef "bass"

c g' <c e> g

c, g' <bes e> g

c, g' <bes e> g

f c' <e a> c

f, c' <e a> c

g d' <f b> d

g, d' <f b> d

c, g' <b e>2

score is the top-level object including everything. The second level includes global settings, besides the staffs.

Each staff defines a line of notes and descriptions of how to synthesize it. The instrument field tells Python how to initialize the instrument to play the notes. It is literally Python code which is evaluated using exec() internally. Here Arachno is a soundfont which is deployed inside the SF2 directory. The index tells which preset to use (40 = violin, 0 = piano).

Inside the content filed, LilyPond notes are embedded as a multiline string.

Since version 1.0.3, a command-line tool scoredraft is provided to process the YAML input.

usage: scoredraft [-h] [-ly LY] [-wav WAV] [-meteor METEOR] [-run] yaml

positional arguments:

yaml input yaml filename

optional arguments:

-h, --help show this help message and exit

-ly LY output lilyond filename

-wav WAV output wav filename

-meteor METEOR output meteor filename

-run run meteor

With scoredraft -ly, the YAML file can be converted to a regular LilyPond file, which can be further improved for publishment. More information besides the notes can be passed to the synthesizer engine, which doesn’t necessarily go into the LilyPond file.

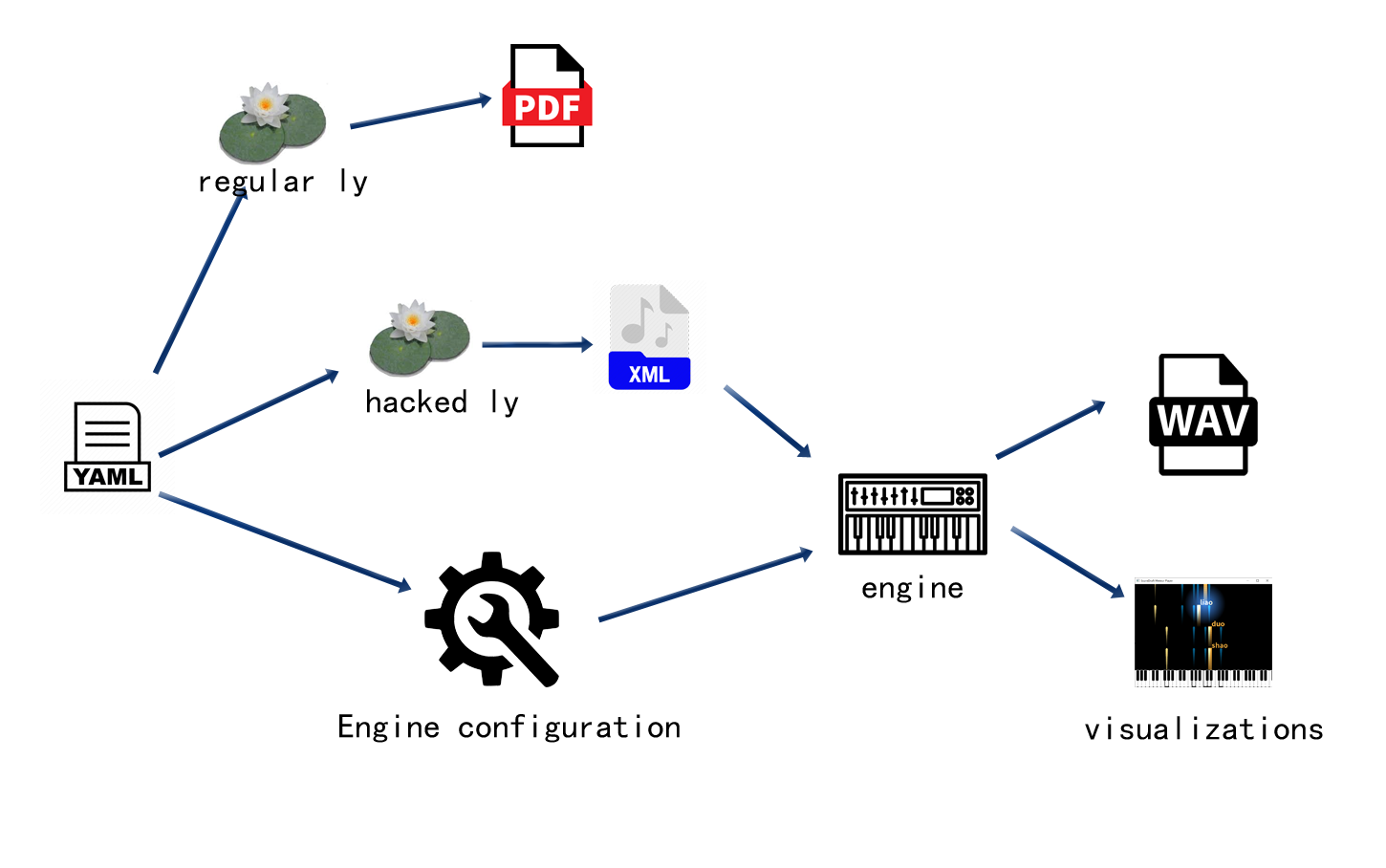

The picture above shows the internal workflow how a YAML file gets processed. The workflow allows arbitrary information (useful to the synthesizer) to be included into the YAML file. For example, we can add pedal movements like:

# exmaple 2

score:

tempo: 150

staffs:

-

relative: c''

instrument: Arachno(40)

content: |

r4 g c d

e2 e2

r4 e dis e

d2 c2

r4 c d e

f2 a2

r4 a g f

e2. r4

-

relative: c

instrument: Arachno(0)

content: |

\clef "bass"

c g' <c e> g

c, g' <bes e> g

c, g' <bes e> g

f c' <e a> c

f, c' <e a> c

g d' <f b> d

g, d' <f b> d

c, g' <b e>2

pedal: |

bd1

bd1

bd1

bd1

bd1

bd1

bd1

bd1

There is a dedicated syntax in LilyPond for pedals. However, there’s no tool that can reliably convert that syntax into MusicXML. Therefore, instead, we simply define it as a percussion sequence, where bd means base-drum. You can use other percussion notes too, there’s no difference since a pedal is just a simple trigger.

For guitar tracks, we often want to add a little delay to the chord notes to simulate sweeping. This can be configured by adding a “sweep” field:

# exmaple 3

score:

tempo: 150

staffs:

-

relative: c''

instrument: Arachno(40)

content: |

r4 g c d

e2 e2

r4 e dis e

d2 c2

r4 c d e

f2 a2

r4 a g f

e2. r4

-

relative: c

instrument: Arachno(24)

sweep: 0.1

content: |

\clef "bass"

c4 e <g c e>2

c,4 e <g bes e>2

c,4 e <g bes e>2

f,4 a <e' a c>2

f,4 a <e' a c>2

g,4 b <d g b>2

g,4 b <d g b>2

c4 e <g b e>2

sweep: 0.1 tells ScoreDraft to add a 10% delay to chord notes.

To include a percussion track, simply add is_drum: true then you can use the percussion notes:

# exmaple 4

score:

tempo: 150

staffs:

-

relative: c''

instrument: Arachno(40)

content: |

r4 g c d

e2 e2

r4 e dis e

d2 c2

r4 c d e

f2 a2

r4 a g f

e2. r4

-

relative: c

instrument: Arachno(24)

sweep: 0.1

content: |

\clef "bass"

c4 e <g c e>2

c,4 e <g bes e>2

c,4 e <g bes e>2

f,4 a <e' a c>2

f,4 a <e' a c>2

g,4 b <d g b>2

g,4 b <d g b>2

c4 e <g b e>2

-

is_drum: true

instrument: Arachno(128)

content: |

bd4 hh sn hh

bd hh sn hh

bd hh sn hh

bd hh sn hh

bd hh sn hh

bd hh sn hh

bd hh sn hh

bd hh sn hh

For percussion tracks, the instrument field must be a GM Drum instrument like the one used here.

For singing synthesizing, some different configuration fields are needed:

# example 5

score:

tempo: 150

staffs:

-

relative: c'

is_vocal: true

singer: TetoEng_UTAU()

converter: TTEnglishConverter

content: |

r4 g c d

e2 e2

r4 e dis e

d4 (c) c2

r4 c d e

f2 g4 (a)

r4 a g f

e2. r4

utau: |

ju Ar maI

s@n SaIn.

maI oU nli

s@n SaIn.

ju meIk mi

h{p i.

wEn skaIz Ar

greI.

-

relative: c

instrument: Arachno(0)

content: |

\clef "bass"

c g' <c e> g

c, g' <bes e> g

c, g' <bes e> g

f c' <e a> c

f, c' <e a> c

g d' <f b> d

g, d' <f b> d

c, g' <b e>2

pedal: |

bd1

bd1

bd1

bd1

bd1

bd1

bd1

bd1

-

is_drum: true

instrument: Arachno(128)

content: |

bd4 hh sn hh

bd hh sn hh

bd hh sn hh

bd hh sn hh

bd hh sn hh

bd hh sn hh

bd hh sn hh

bd hh sn hh

First, set is_vocal to true. Second, instead of defining a instrument, here we need a singer. Most of the cases, a converter needs to be given to handle syllable connections. If the voicebank is defined in CZMode, simply add CZMode: true. Third, add an utau field to include the phonetic symbols. Syllables are separated by spaces, with a dot at the end of each sentence. A rest ‘r’ in the content code also marks the end of a sentence. Each syllable is mapped to 1 note by default. Slurs can be used so that multiple notes can be mapped to a syllable.

Reference

Currently, there is only a small set of YAML keys recognized by ScoreDraft, and basically everything has been mentioned above. Here is a exhaustive list of all keys.

score

The top-level object

tempo

Global property defining tempo in BPM.

title

Title of the score. (for LilyPond)

composer

Author of the score. (for LilyPond)

staffs

Entry to the array of staffs.

content

Staff property containing embedded LilyPond code. Basically any LilyPond code can be put here. For -ly output, these code will be put straightly to the ly file. However, for the synthesizer, only a small part of LilyPond syntax is acknowledged. Besides the notes, <> is recognized as a chord, and () is recognized as slur. Slurs are useful for singing synthesize.

is_drum

Staff property indicating whether the current staff is a percussion track.

is_vocal

Staff property indicating whether the current staff is a singing track

When neither is_drum nor is_vocal is set, the current staff is a instrumental track.

relative

Staff property for a instrumental/singing track, indicating the content is in relative mode.

instrument

Staff property for an instrumental/percussion track, giving instrument information.

The value should be literal Python code calling the instrument initializer.

For percussion tracks, the instrument should be a GM Drum instrument.

pedal

Staff property for an instrumental track, telling the movement of the sustaining pedal. The value should be written using arbitrary percussion notes. Rests are supported.

sweep

Staff property for an instrumental track, adding a delay to chord notes to simulate a guitar sweeping effect.

singer

Staff property for a singing track, giving singer information.

The value should be literal Python code calling the singer initializer.

converter

Staff property for a singing track, giving the Python variable name of the lyric converter required by the singer.

CZMode

Staff property for a singing track, indicating whether the singer is in CZMode.

utau

Staff property for a singing track containing UTAU phonetic symbols for each syllable. Syllables are separated by spaces, with a dot at the end of each sentence.

volume

Staff property for any track. Volume value used by the mixer.

pan

Staff property for any track. Pan value used by the mixer.